I arrived at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City two hours before closing, so only had time to see half the items on display. Out of all the amazing pre-Colombian artefacts, my favourite was the 3-metre-tall basalt sculpture of Coatlicue, the Aztec goddess who gave birth to the moon, stars, and Huitzilopochtli, the God of War. Her name means skirt of snakes.

The photo I took of the sculpture is crap. But I forgive myself, as the low lighting and the ban on using flash made it hard to take good photos. The lighting to protect the artefacts is understandable, but it combined with the small text on explanatory panels and captions to make reading hard. When I realised I needed to speed up because closing time was approaching, I switched from reading the Spanish to English—when it was available. But the English text was even smaller. Without a doubt, Mexico City has the best museums of any city I’ve been to, both in terms of range and quality. However, the presentation of written information at the Museum of Anthropology, Museum of the Templo Mayor, and the Museum at Teotihuacan could be better. My wife thinks money from entrance fees is being stolen rather than being spent on the upkeep of the museums. Despite this, I give Mexico City a 9.5 out of 10 for its museums.

Reading Gary Jennings’ monstrous 400,000-word historical novel, Aztec, it’s a sure bet he spent a lot of time conducting research in the Anthropology Museum. Aztec is as famous for its sex scenes as it is for its historical detail. As yet, I’ve found one 21st-century cancel culture review of the novel. This reviewer found nothing more to this huge book than a story about a man and his penis, and compares Aztec to the film Boogie Nights. Aztec is narrated by Mixtli, an Aztec scribe, asked to tell of his life and times so the Bishop of New Spain (Mexico) can send this history back to the King of Spain. It’s an immensely rich story, giving an unparalleled overview of the complexities of religion, trade, love, and war in the last days of the Aztec Empire. However, the Bishop, in his letters that accompany installments of the narrative, only tells the king how outraged he is over the tales of sex and human sacrifices. He sees nothing of value in the Aztec world. He is blind like a cancel culture reviewer trawling old books looking for sexism and racism and finding them…and nothing but. In my reading, Aztec is full of strong female characters. That’s not to say Jennings can’t be criticized for many things, but boiling this epic down to a man and his penis is insanely reductive. This author puts everything in, he’s not good at leaving stuff out—and obviously, a lot of sex went on in Aztec society, but sex, much more so than violence, gets people in a tizz. But look here, it’s OK to read this even if it’s written by a white American middle-aged man (the horror) (who spent 12 years researching and may actually know stuff) because it’s an ANTI-COLONIAL text. In Mexico, they know it’s good, and I saw it on sale at the bookshop in the former Dominican Convent (amusing) in Tepoztlán and at a stall in the same town’s market.

Jennings’ description of the sculpture of Coatlicue in Aztec is outstanding. He weaves it into his story by attributing its creation to one of his characters.

“Since Coatlicue was, after all, the mother of the god of war, most earlier artists had portrayed her as grim of visage, but in form she had always been recognizable as a woman. Not so in Tlatli’s conception. His Coatlicue had no head. Instead, above her shoulders, two great serpents’ heads met, as if kissing, to compose her face: their single visible eye apiece gave Coatlicue two glaring eyes, their meeting mouths gave Coatlicue one wide mouth full of fangs and horribly grinning. She wore a necklace hung with a skull, with severed hands and torn-out human hearts. Her nether garment was entirely of writhing snakes, and her feet were the taloned paws of some immense beast.”

And those taloned paws have animal eyes too—the feet of this God have been zoomorphised. I’ve heard the word anthropomorphised many times, but never zoomorphised until I watched this video with an excellent explanation about the sculpture of Coatlicue.

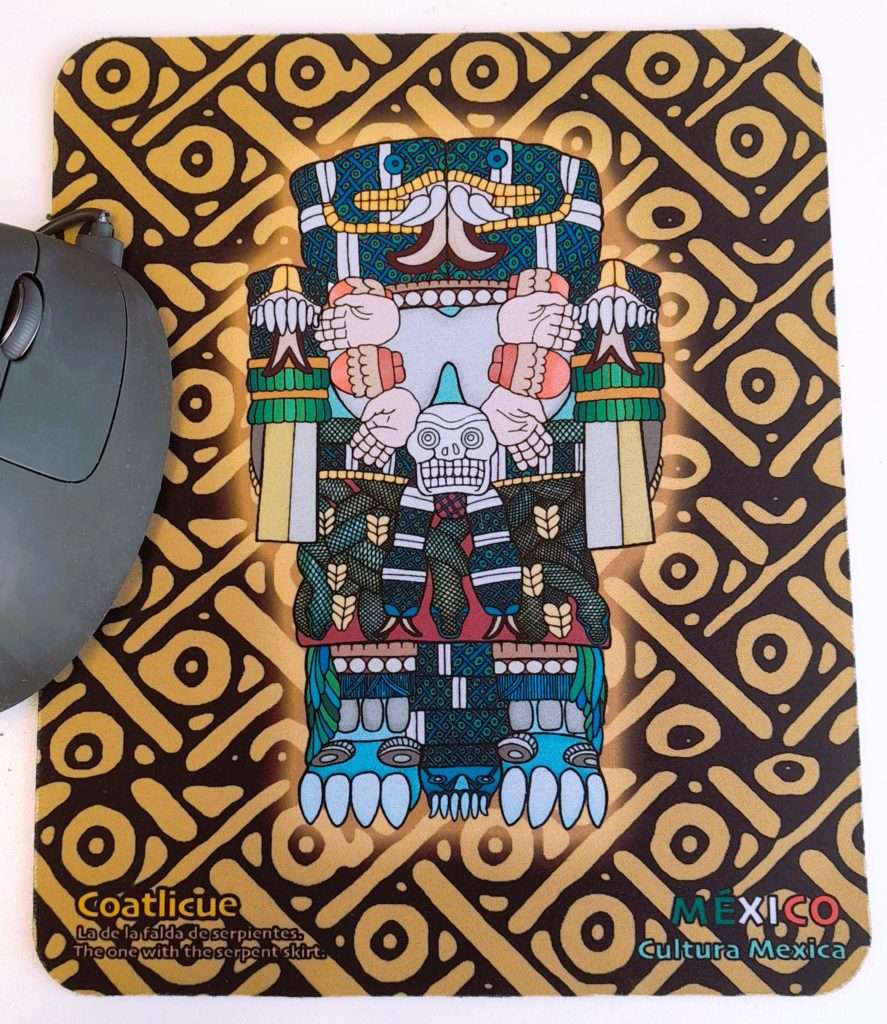

At a quarter to six, guards at the museum started to politely shoo visitors out of the exhibitions. We moved onto the packed gift shop in the main foyer. I was delighted to find a mousepad with an image of Coatlicue as she appears in the sculpture but in bright colours. This is not unrealistic, as the sculpture would have once been painted. I got the mousepad for the not unreasonable price of 140 pesos, 14 NZD, or 8 USD.