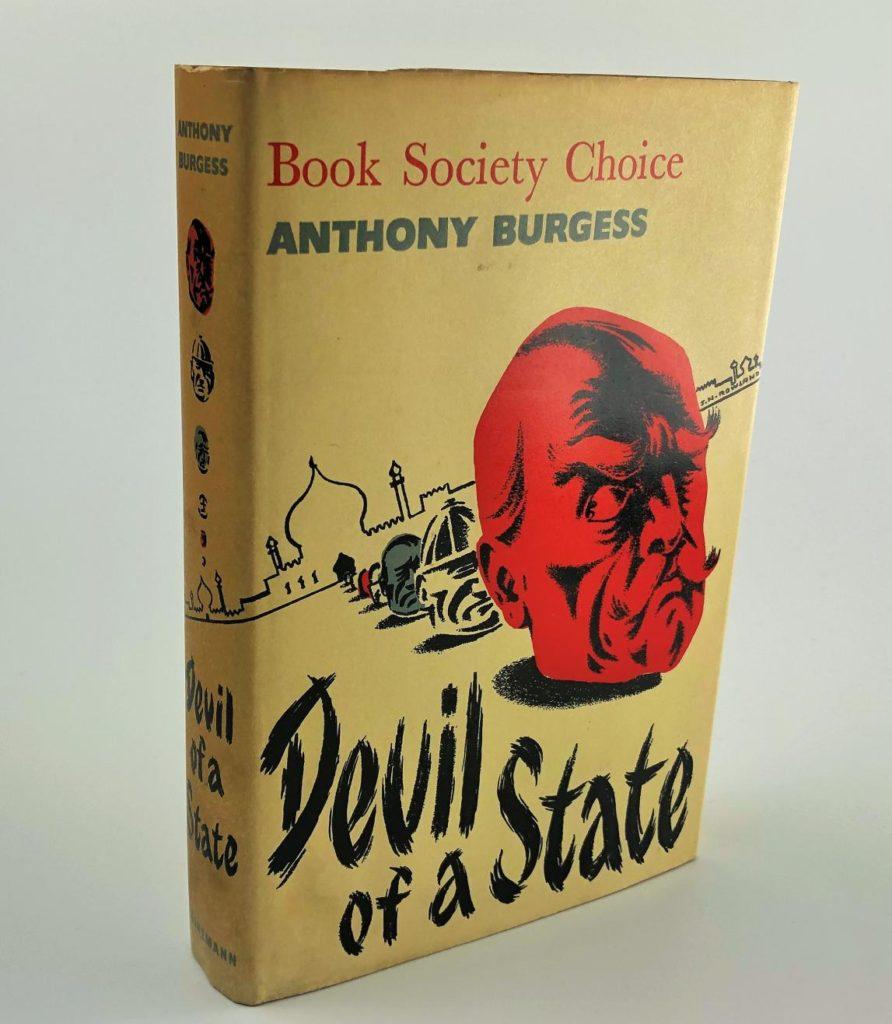

Devil of a State, published 1961, is set in Dunia, a fictional East African state on the verge of independence. In this novel Burgess draws on his experiences as an Educational Officer in the Sultanate of Brunei where the original manuscript was set. Fearing a possible libel case, the publisher, Hutchinson, had Burgess change the setting. This may have been a good move because one of his earlier works about Malaya had provoked a lawsuit and another novel Burgess published in 1961, The Worm and the Ring, about an English grammar school, was pulped because of libel.

Initially, I feared the change of scene would make this novel lack depth, because, for example, Burgess could not use his knowledge of Malay, which he did in his novels set in Southeast Asia. Brunei, a tiny country on the island of Borneo, has Malay as its national language. In the first chapter Lydgate, the main character, calls out for a “taksi” to stop, this being the Malaysian spelling, but beyond this Burgess doesn’t use any Malay words, instead he refers to Dunia’s national language. Unlike in Clockwork Orange, he doesn’t invent a new tongue, but lets us know which language is being spoken and relates the dialogue in English. Dunia is quite convincing as a small, ramshackle, Islamic country transitioning slowly out of the colonial era relying on its uranium mines for income. There are plenty of Chinese, Indian and Arab immigrants chowing down on greasy noodles and curry. For the Africans he comes up with some invented ethnicities such as the Potok and there are other fictional (presumably) British colonies mentioned, where Lydgate has previously been posted. One alcoholic District Advisor has a rather tough posting:

“Rowlandson had an awkward territory. It was on the very fringe of Dunia; across a river hardly wide enough for a natural frontier with the jungles of Shurga; south lay Trognika, marked off from the United-Nations-protected land by the third parallel of latitude.”

Burgess hilariously lampoons how people speak English; luckily, some of the best dialogues of this sort involve Australians rather than non-native speakers, and so we are on safe ground enjoying the send up of Aussie road-builders, engineers and foremen upset that the pommie Lydgate has bought up their convict past:

“I told him that sort of thing was the sort of thing that’d mike any good Aussie go a bit crook, I said. And I said that not everybody kime to Austrylia on prison-ships. And then he sort of said how he was only kidding.”

Burgess has Aussie speech well-recorded here: mike (make) and kime (came) are spot on in terms of phonetics, although the Antipodeans wanting to be the salt of the earth (about 80 percent of us) use come for present and past tense. The ‘sort ofs’ are another scourge of Antipodean speech — endless qualifiers. I’m forever having to edit ‘a bits’ out of my own writing. I would render Burgess’s Austrylia instead as Austraya, they definitely don’t pronounce the ‘l’ and it’s often reduced to Straya.

The most entertaining characters are an Italian father and son duo, Nando and Paolo Tasca, contracted to install marble in the mosque the chain-smoking Caliph of Dunia is building. The mosque is a symbol of the Caliph’s power and supposed religiosity — it’s all he is really concerned with, any other problems he wants the UN Advisor, Tomlin, to handle. The Caliph gets rid of Tomlin when he refuses to deal with Paolo Tasca, camped in the mosque’s minaret as a bizarre form of protest. The older Tasca, Nando, spends his time drinking beer, making his son, who he hates, do all the work at the mosque. Paolo for his part has trouble getting laid in a Muslim state with no obvious prostitution. He ultimately finds a woman willing in Elaine, the African wife of Forbes, the Aussie roadman outcast for having a black wife. Forbes has ‘rescued’ Elaine from prostitution and refuses to believe she is still on the game while he is at home looking after the kids. He is the kind of gullible character you might, to this day, find sitting on a bar stool in Thailand.

Nando Tasca speaks more English than his son and in recreating his speech patterns Burgess is on relatively safe ground:

“I not a ave a you in a my ouse. In a the war we ave a foreign men in Italy. I not a ave one in my ouse. They not a ave a good manners. I not a have a you in a my ouse so you not a say what a you say just a now.”

With the Chinese Carruthers Chung he is on shakier ground. Carruthers is a fluent English speaker who merely mixes his ls and rs — more a Korean or Japanese trait than a Chinese one. Here the book almost falls to the level of the 1970s British comedy Mind Your Language about a night school English class full of foreigners with funny accents. But the mixing up of the rs and ls makes for some fun misunderstandings e.g. to pray becomes to play. Carruthers invites Lydgate to his bridge club, on arrival Lydgate learns that new members have to confess their sins. Dunia’s Passport Officer, the fifty year old Lydgate, often married and changing countries has a lot to confess. A guilt wracked protagonist is just about a necessity for the Catholic Burgess, and if no guilt is present then it has to be installed, hence Alex’s ‘treatment’ in Clockwork Orange. The best linguist in Dunia is hotel receptionist George Lim, who translates the German instructions for how to fix the marble cutting machine for Nando Tasca. Like the Australians, a strong voice for philistinism, Nando declares: “It a not a right a Chinese know a German.”

Paolo Tasca becomes involved in a workers strike and is beaten up in a melee with police and the Australian road crew taking revenge for his dalliance with Forbes’s wife. Once recovered, Paolo returns to the mosque, still shut after the strikes, and climbs the minaret. Singing Italian songs and cursing his father through the loudspeaker normally reserved for the call to prayer, he becomes a hero for the workers and the bearded men who are not going to shave until independence and are possibly planning a revolution. This backstory is not fully developed, nor is Lydgate’s past in various other countries, but the partial picture is enough. Lydgate insulted his current boss, Mudd, in Shurga, which is one reason he is exiled from the European district on the hill. The other problem is that he, like Forbes, has an African partner — although she is up the river having a baby. Lydgate dreams she is bringing him the smoked head of Mudd as a present, and there is another subplot about Europeans going up river and getting beheaded. This thread likely came out of stories of Dayak headhunters in Borneo’s interior that Burgess heard in Brunei. One of those to get beheaded and eaten is the unfortunate Rowlandson.

Lydgate briefly makes it to the hill when his thirty-something Australian wife, Lydia, returns to Dunia and convinces him to live with her. Lydgate isn’t much interested in staying with Lydia and escapes her easily. He plans to leave Dunia too, but eventually gets his comeuppance. The climactic chapter for Lydgate is disappointing, this is a book where the subplots — the Italians, the UN Advisor, Forbes — are more interesting than the main plot.

I haven’t read the Malayan Trilogy for fifteen years, but the Burgess who wrote those books was concerned for how independence would turn out and hoped for harmony between the Malays, Indians and Chinese. He was also more serious about Islam, claiming even to have considered converting. The switch from Malaya to Brunei wasn’t wise because here, in his fourth novel about life in the tropics, the corruption, heat and alcohol have got to him. Perhaps Southeast Asia had become a broken dream; he had seen paradise when he first arrived in the variety of cultures, the sun and the possibility of sexual freedom; also the colonial service compared well to the dullness of his job at Banbury Grammar School.

Then there were the real life shenanigans of his dipsomaniac and nymphomaniac wife, Lynne, drinking more gin than an isolated Englishman up the Yangtze in a Somerset Maugham story. Burgess recounts in his autobiography that one day in Brunei he lay down on the floor of his classroom pretending to be sick so he could go home to England. Whether he really was faking it is hard to say, since he was later diagnosed with a brain tumour — which in turn was an incorrect diagnosis. In the end, Devil of the State, dedicated to Graham Greene — who didn’t much like it — is a highly entertaining romp with a rather flimsy plot.